Unbridled risks: the top equine claims risks every owner should know

Unbridled risks: the top equine claims risks every owner should know

When it comes to insuring your horses, understanding the most common and costly claims risks allows you to recognise and prevent them. Equine insurance claims often fall into two major categories: Mortality which refers to the death of the horse and, Life-Saving Surgery (LSS) which refers to emergency procedures to save the horse’s life.

This article takes you through each condition driving these claims—and what you, as a horse owner, can do to reduce the risks.

When instinct takes the reins – the unpredictability of horses

Whether we’re talking about thoroughbreds, pacers, showjumpers, dressage or cutting and reining horses, they are all by nature, incredibly unpredictable. Being prey animals, they have an innately strong fight or flight response. Even the most well-trained or calmer natured horses can be easily spooked.

Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds and sport horses are powerful creatures with high athletic demands. Disciplines such as horse racing, show jumping, eventing, dressage and Western horse disciplines put significant physical pressure on the horse’s body. Joints, tendons and bones are pushed to their limits which make them more injury prone.

The complex anatomy of horses contributes to their high-risk nature. Their digestive systems are particularly sensitive and make them predisposed to conditions such as colic and colitis. Foaling also comes with significant risks of uterine tears, dystocia and emergency C-sections. Even in safe, well-managed environments, horses manage to get caught in fencing, slip in paddocks after heavy rain or get injured from other horses.

The following equine conditions and the recommended prevention and treatments are detailed by Dr Andrew Dart, a highly respected veterinary surgeon specialising in equine health. With over 40 years of experience in veterinary medicine, his knowledge is second to none.

Mortality claims: the leading causes of equine death

Colic

There are over 70 different causes of colic (abdominal pain in horses). This makes it one of the most prevalent claims risks in the equine industry. Most horses tend to suffer with this at some stage during their life, it often going unnoticed and resolving itself. The abdominal pain caused by colic therefore ranges from mild (pawing the ground, lying down, and looking at the abdomen) to severe (rolling and uncontrollable pain).

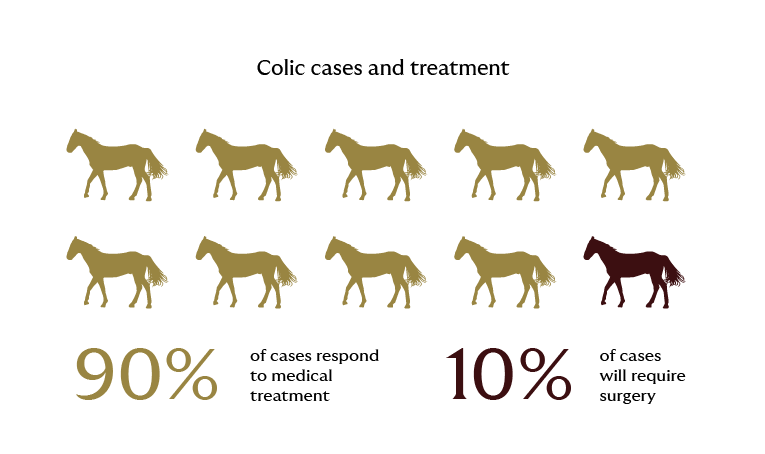

90% of cases respond to medical treatment from your veterinarians including, but not limited to, pain relief and fluids, and electrolytes administered by a stomach tube and/or intravenously.

However, 10% of cases will require surgery. Anaesthesia and surgery have improved significantly over the past 40 years and survival rates after surgery are generally good.

Early intervention is key to a positive outcome.

How can I reduce the risk of my horses suffering from colic?

- Ensuring a consistent, good quality high fibre diet

- Access to clean water

- A regular feeding program and daily routine

- Regular worming and teeth maintenance

Colitis

Signs to watch out for that are typical of colitis are a dull demeanour, inappetence, high temperature, high heart rate, severe dehydration, and profuse watery diarrhoea. Stabled racehorses are particularly prone to this, that are on low fibre high grain diets and may be being treated with antibiotics, particularly oral antibiotics, for another problem. This leads to a bacterial imbalance and an inflamed colon. The damaged colon will lose large volumes of fluids, electrolytes, and protein and therefore absorb endotoxins produced by the bacteria.

This causes severe diarrhoea, dehydration and shock - rapidly progressing to death.

What is the best treatment?

Early hospitalisation and treatment with large volumes of intravenous fluids and protein (plasma) and addressing the endotoxemia.

Prevention

- A fibre-rich diet

- Judicious use of antibiotics under veterinary direction

- A low stress environment

Stress fractures

Stress fractures are a common problem in young thoroughbred racehorses during their first few preparations. When first entering training, their bones must remodel to meet the intense biomechanical stress of racing. The bones under the greatest stress undergo a period of demineralisation (weakening), followed by remineralisation (laying down bone in a more structurally efficient design), to remain light weight, but optimise biomechanical strength. Initially the bones are not ready for sustained repetitive biomechanical forces and so in the first 6-12 months of training they are more susceptible to fractures.

If a stress fracture is not diagnosed, then the horse will often return to work and this cycle of work and lameness continues. Horses will then often sustain a full and catastrophic fracture of the bone. “Bucked shins” or “shin soreness” is the most common form of a stress fracture, but the humerus, tibia, radius, pelvis, and vertebrae are bones commonly involved.

Being ahead of the curb

In preparing young horses for racing, it is crucial to recognise cardiovascular fitness, and muscular development will progress more rapidly than bones can adapt to the biomechanical forces of training and racing. Understanding the disease process and allowing time for bones to remodel and adapt to these biomechanical forces in young horses, is key to reducing orthopaedic injuries.

A gradual increase in work, particularly in young horses, looking for any early signs of lameness, combined with early intervention and diagnosis, are fundamental to prevention of fractures.

Degenerative joint disease (DJD)

This is also known as arthritis. All joints undergo degeneration from wear and tear throughout a horse’s life. Horses engaged in disciplines that are associated with intense exercise will be more susceptible to DJD and at a younger age. Intense exercise can lead to joint inflammation and progressive damage to the cartilage and bone within the joints, predisposing to a more severe injury. Initially, the changes go unnoticed but later results in joint effusion (excess fluid in the joint), pain on joint flexion, reduced range of motion and ultimately lameness.

It’s a joint effort – preventative measures for DJD

These changes are irreversible and progressive but can be minimised with good training programs that minimise exercise at maximum effort, and by employing strategies to reduce the impact on the joints. There are also various drugs that can improve joint health and slow down changes.

These are most effective when they are started in young horses entering training and used regularly during periods of exercise. When indicated, surgery can be performed to remove chip fractures and clean up areas of cartilage and bone degeneration.

Septic joints/tendon sheaths

Joints and tendon sheaths contain synovial fluid which is a viscous lubricant. Tendon sheaths are filled synovial fluid pads that surround tendons to prevent damage as the tendon passes over joints.

Infection in these structures is an emergency.

Infection can enter due to trauma or even through a small puncture wound. Bacteria multiply and there is often a delay between infection and the development of clinical signs. Early diagnosis and treatment are fundamental to achieving a good outcome. The joints and tendon sheaths of the lower limbs are most susceptible to trauma, and these regions are the most common in adult horses. In foals, systemic infection from diarrhoea, lung infections or infected umbilical remnants can enter the blood stream and localise in any joint or tendon sheath.

Navigating Life Saving Surgery (LSS) Claims: timely decisions and life-saving outcomes

Colic, colitis and septic joints/tendon sheaths can all require LSS. In addition, these conditions make up the top LSS Claims:

Emergency C-Section

Foaling in horses, unlike other species, is a dynamic and violent event. Timely decisions are vital. Where there is no prospect of repositioning the foal to facilitate delivery, a caesarean section is the often the only option to save the mare and foal.

Early intervention is critical if the foal is to be saved.

The surgery must be performed under general anaesthesia and at a surgical facility that offers 24-hour care.

Uterine tears

Mares can sustain trauma during foaling including uterine tears. These can vary from small punctures to large tears and initially may go unnoticed, even for several days, before the mare begins to show signs of septic peritonitis. This is characterised by a dull demeanour, an elevated heart rate and temperature and, in some cases, signs of mild abdominal pain. Sometimes the mare may prolapse intestine through the tear or out of the vagina. Abdominal surgery is usually required to repair the tear and address the peritonitis.

The prognosis depends on the size of the tear and severity of the peritonitis. Early diagnosis and intervention will improve the prognosis for survival and improve the prospects for future breeding.

Post-foaling uterine haemorrhage

During foaling mares can rupture the middle uterine artery, which is found in the broad ligament of the uterus. Older mares and those that have had multiple foals are at a higher risk. Haemorrhage may remain contained within the broad ligament which helps slow the bleed, or the broad ligament may rupture leading to ongoing haemorrhage into the abdominal cavity. In the first 12 hours after birth, signs in the mare of internal haemorrhage include dullness, an elevated heart rate, pale mucus membranes with slow refill time and sometimes sweating and mild abdominal pain that may progress to ataxia and recumbency. On ultrasound of the abdomen swirling fluid can sometimes be seen - a peritoneal fluid sample will show frank blood and on rectal examination there may be a large mass felt within the broad ligament.

Treatment includes keeping the mare quiet, use of drugs that promote coagulation, whole blood transfusions, regulated intravenous fluid therapy, antibiotics, and pain relief.

Mares that have had a history of post-foaling haemorrhage are at increased risk of future episodes during foaling.

Severe lacerations

Horses by nature, are at risk of sustaining lacerations, particularly of the lower limbs. Generally speaking, wounds to the body heal well, while wounds to the lower limbs in horses are prone to poor healing and production of excessive granulation tissue. Muscle cover in the lower limb of the horse is minimal and this makes joints, tendon sheaths along with tendons and ligaments, more exposed to injury.

Penetration of synovial structures including joints and tendon sheaths are emergencies.

Bandages and pressure can minimise excessive haemorrhage and provide protection while a veterinarian is called. The decision to try and close the wound primarily (suture the wound closed), partially close the wound (leave an area open to drain or to heal by second intention) or to allow the wound to heal as an open wound, is made based on the time since injury, the site, the degree of damage, the loss of tissue and skin, the degree of contamination, and the cost benefits.

Average price estimates of surgeries based on veterinary sources and typical pricing ranges in Australia

| Procedure | Estimated cost (AUD) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Colic surgery | $12,000 – $20,000 | Includes anaesthesia, surgery, and post-op care |

| Colitis treatment (non-surgical) | $6,000 – $10,000 | Intensive medical management with IV fluids, plasma, etc. |

| Septic joint/Tendon sheath lavage | $5,000 – $10,000 | Requires arthroscopic lavage and hospitalisation |

| Emergency caesarean section | $10,000 – $18,000 | Includes general anaesthesia, surgery, and neonatal care |

| Uterine tear repair | $6,000 – $12,000 | Cost varies based on severity and peritonitis management |

Thoroughbreds and sports horses are a significant financial asset that come with undeniable risks. From sudden medical emergencies like colic to foaling complications that require surgery, the unpredictability of horses is a constant undercurrent in equine care. Understanding the most common equine insurance claims – mortality and life-saving surgery – can equip you to make informed decisions about your coverage and risk management.

Get in touch with the Equine team